Since fiscal year 2019, the Department of Design, Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts, and JAKUETS Inc. have been conducting a joint design research project. Led by graduate students from the 7th Laboratory (Design Experience), the project explores new areas of application for the early childhood educational tool “B BLOCK.”

In the second year of the project, fiscal year 2020, seven students each developed their own concepts and turned their ideas into tangible forms under the theme of “designing new parts that expand experiences and broaden the range of users.”

To Observe Experiences and Emotions

The project began in April under the extraordinary circumstances of restricted access to the university due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The student members first encountered B BLOCK at home, a far cry from the lively start of the previous project, where everyone simultaneously came across a pile of pieces at the university (

≫2019年度プロジェクト ).

This time, the members looked at the blocks placed in their own rooms and quietly confronted their presence and sense of strangeness alone. They struggled with the question of what they themselves could do with these blocks.

The study group, which began in May, was also initially held online. After each participant introduced ideas for parts they had drawn at home and went through the process, Associate Professor Yamazaki Nobuyoshi called on everyone to “set aside the word ‘play’ from next time onwards, observe the world, and find and bring to the table some joyful experiences.”

Like the word “design,” the word “play” has many different meanings. Perhaps this was an attempt to avoid that elusiveness.

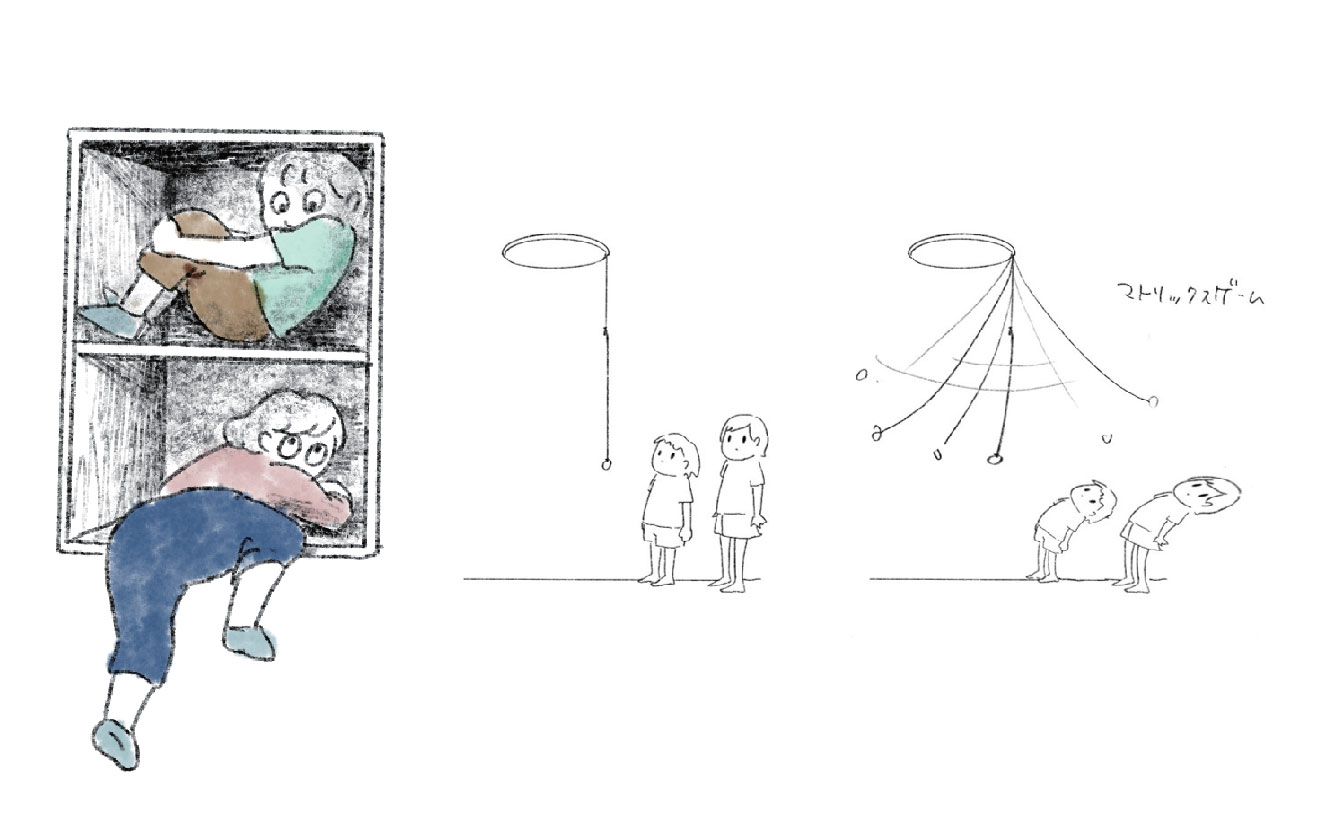

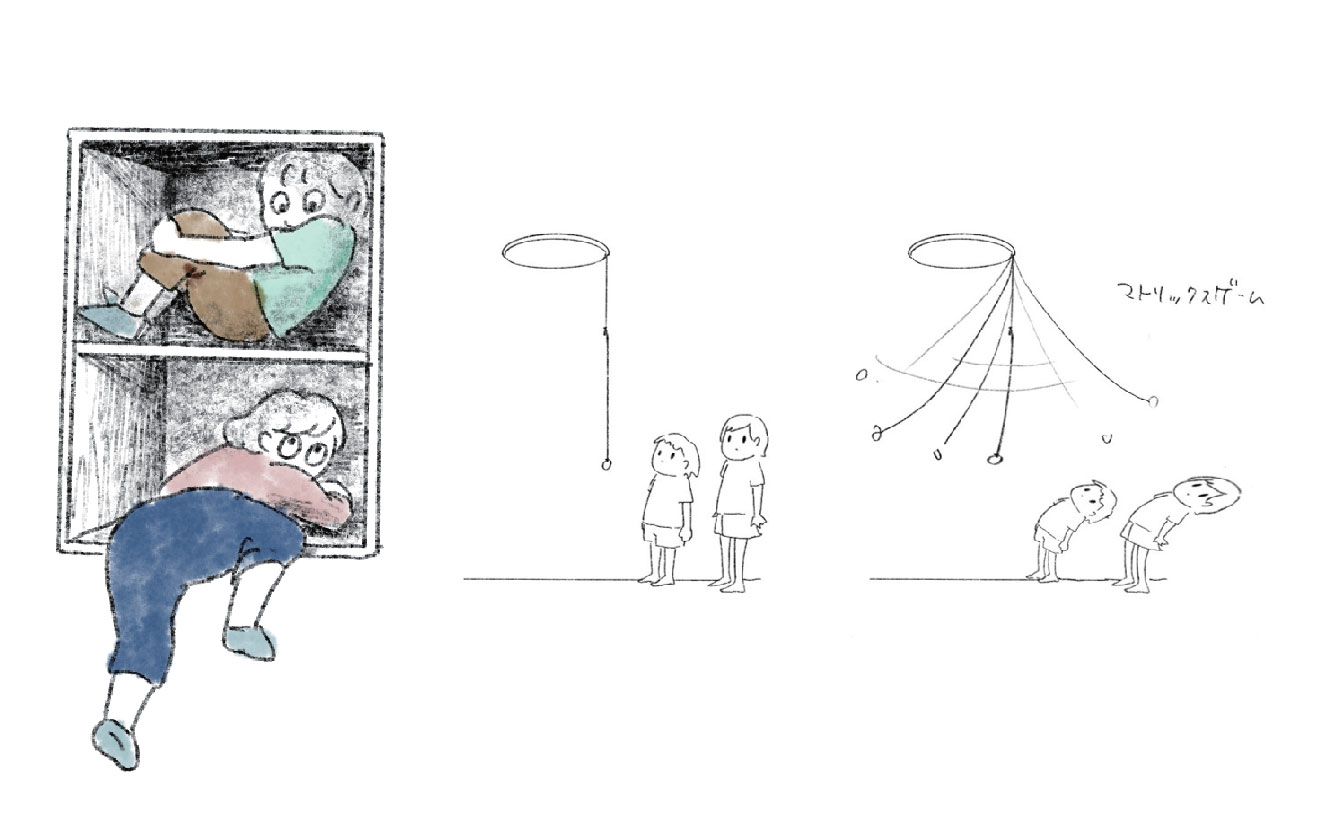

From then on, while keeping in mind the assignment of “new parts,” they repeatedly tried to find and bring together “joyful experiences”—a process that lasted for a full four months. At first, the members’ interests were focused on familiar indoor and outdoor settings, but they soon began to transcend national borders, trace history back, and delve into the online world, casually crossing the boundaries of fields and time and space to include the games played by maiko in tatami rooms and the ingenious design of tea utensils.

While watching each member’s presentation, I felt that they were like travelers endlessly wandering the world, as if unconcerned with the stay-at-home life. At the same time, it was interesting to note that many members also turned their attention to their own pasts, digging up joyful experiences and reflecting on the causes and circumstances behind them.

In other words, the students used their own perceptions as a filter, traveling between the world outside themselves (the outside world / outer space) and the world inside themselves (the inner world / inner space), examining where “joy” exists and how it takes shape, and repeatedly presenting this visually.

When I see a scene expressed by a student in a Tokyo University of the Arts project, I often feel that it is filled with a wealth of information that cannot be fully captured in words. For example, a painting of a joyful experience includes specific elements such as the environment and tools that make it possible, the actions of the protagonist, the passage of time, and the nature of communication with others.

Furthermore, the emotions of the characters that emerge from the integrated space, and the entire scene that encompasses those emotions, are depicted as a scene that the artist gazes upon with both heart and eyes. It even possesses a sense of atmosphere and temperature.

Such a complex and richly layered world, expressed through the sensibilities and emotions of a single person, is quite different from a worldview constructed from the outset by multiple people using words, such as sticky notes. In this project, replacing the word “play” with “a joyful experience” likely made it easier for the members to bring their focus into sharper alignment with the scenes they were observing.

What Do the New Parts Expand?

Building on the fruits of the intensive observations made in the first half of the year, starting in September, each member began narrowing down the experiences they particularly wanted to focus on and the accompanying emotional shifts, linking these to the concepts of the parts.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic was still ongoing, in addition to the study meetings held about twice a month, starting in October, voluntary progress-report sessions were also held every Thursday, with participants gathering in a well-ventilated room to exchange opinions more frequently.

They shared design proposals, imagined the expanded experiences each part would bring, presented their progress and discussed issues that hindered progress, and shared useful knowledge such as techniques and information on outsourcing partners, allowing for positive momentum in the production process.

For the students, many of whom live alone, this space itself may well have been a joyful one. The ideas developed through this stimulating exchange are presented below.

Haraki Yuzuna “Sakizaki”

Climbing to the top of a mountain and planting a flag, or decorating a star ornament at the top of a Christmas tree, are symbols of accomplishment and joy. However, playing with blocks felt too abstract, and I was always left dissatisfied with the finished result. This part was conceived from such thoughts I had in childhood.

Bannen “band”

Humans have been making sounds since prehistoric times. Enjoying sound could be considered an instinct. Sound-producing materials are placed inside the convex parts of the blocks, and the tone changes depending on the color, so that even people with visual impairments can perceive differences in tone. These parts introduce barrier-free perspectives and encourage physical activity.

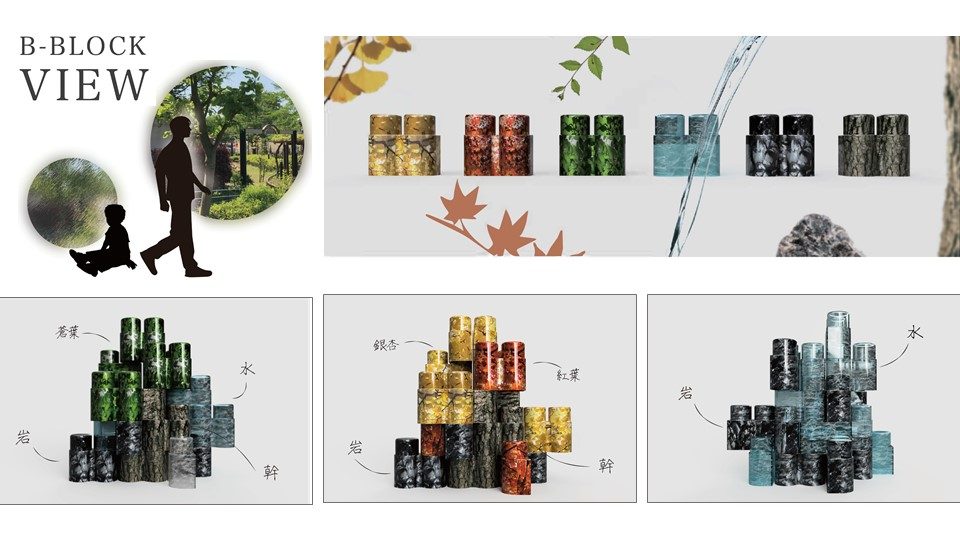

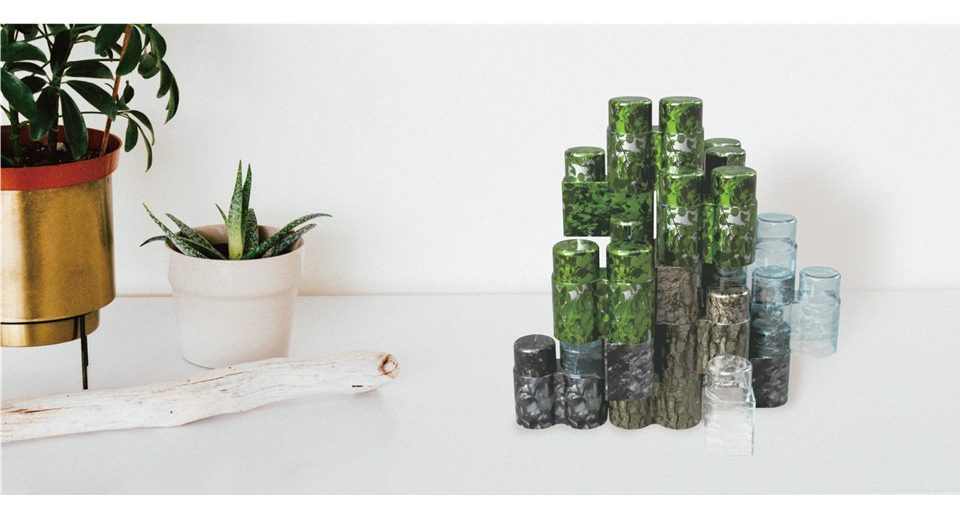

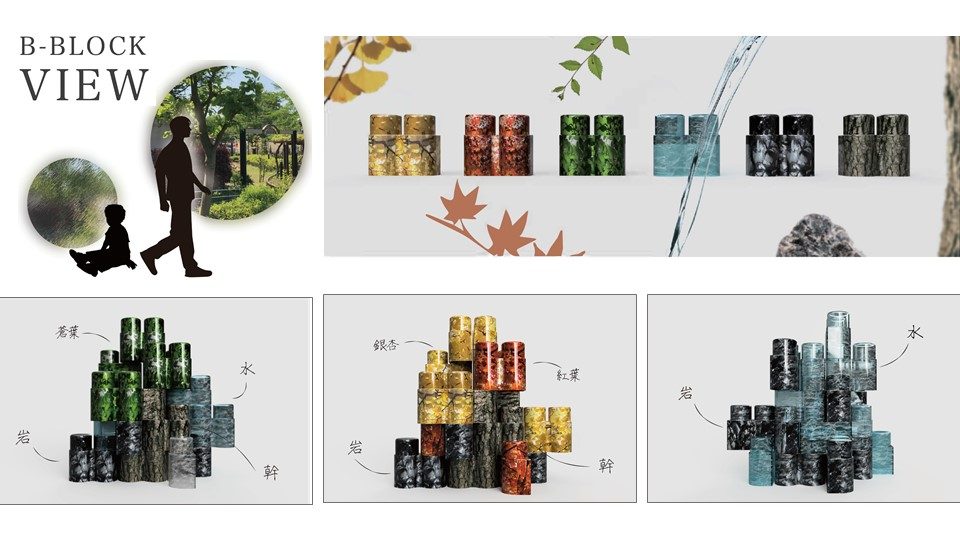

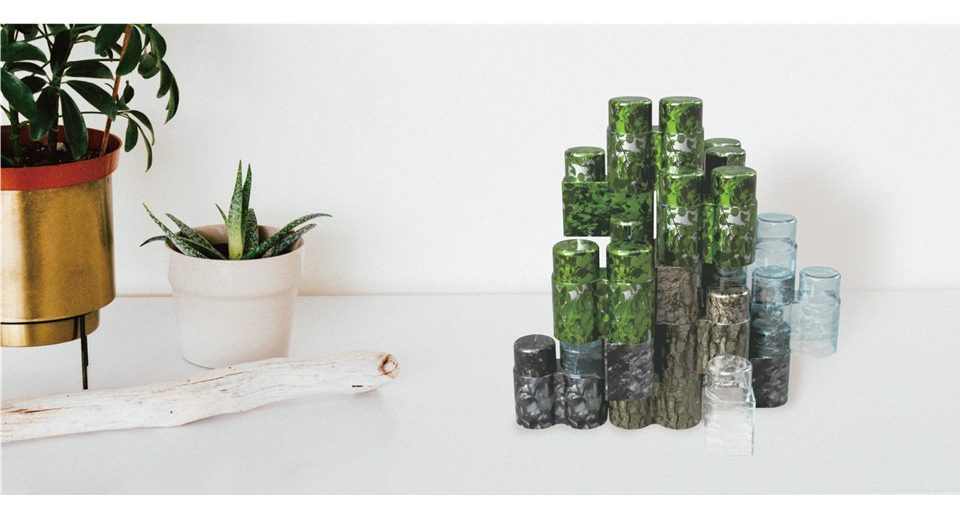

Shimizu Kohei “B BLOCK VIEW”

This proposal calls for “making blocks a pastime for adults.” Children often create artificial objects such as vehicles, houses, and robots. This may be due to the plain surfaces and strong colors of conventional blocks. By using blocks that mimic the textures of nature, adults can create their own version of nature, making blocks something adults, too, can enjoy.

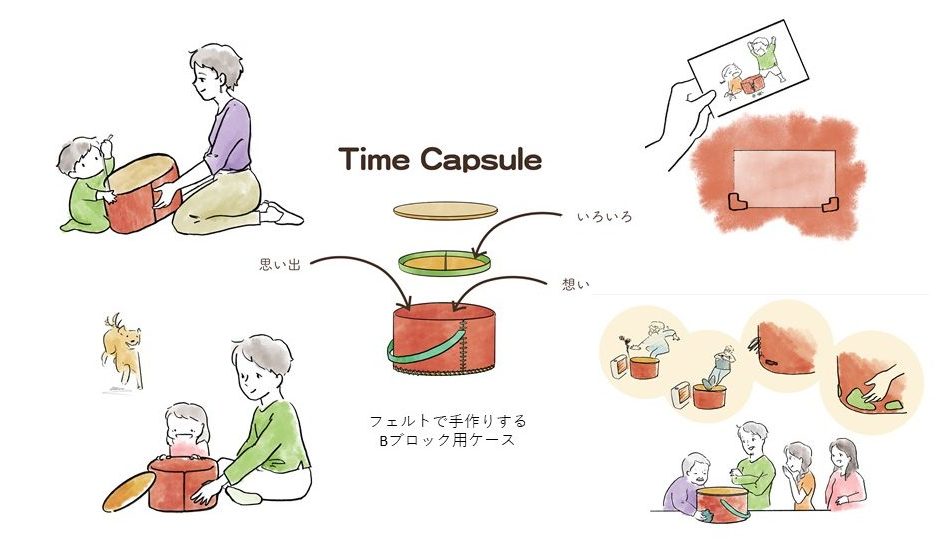

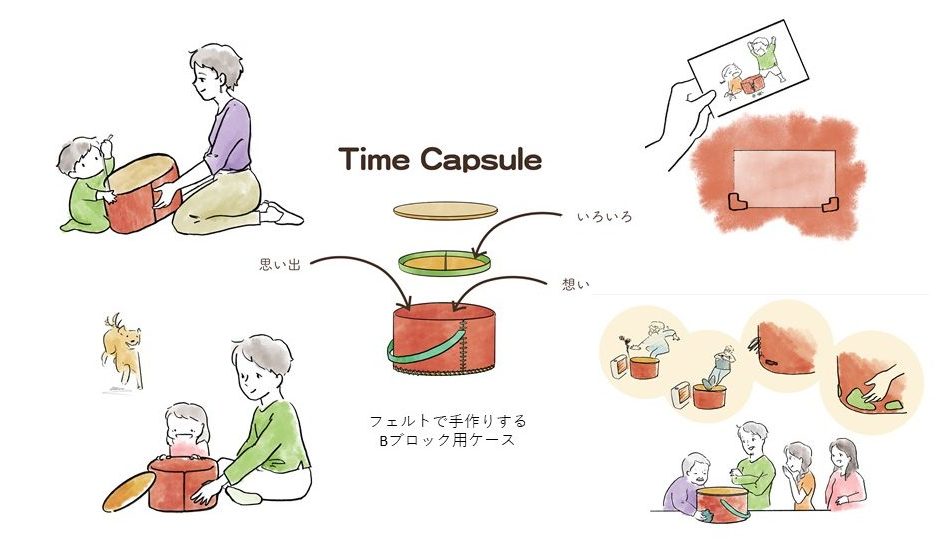

Shinkawa Minami “Time Capsule”

The felt case is provided as a kit that buyers can handcraft together with their families. The soft, warm fabric blends naturally into the interior and records the experiences of time. These traces are passed down from parents to children and grandchildren, fostering communication across generations.

Zheng Moechu “BIO B BLOCK”

“Decaying blocks” made from fungi. They can be made by hand, and once filled with materials, they become usable after about ten days. Because they are made from living organisms, users can enjoy observing how they change over time. By combining them with existing resin blocks, one can experience differences in material qualities, and their potential use as educational materials can also be envisioned.

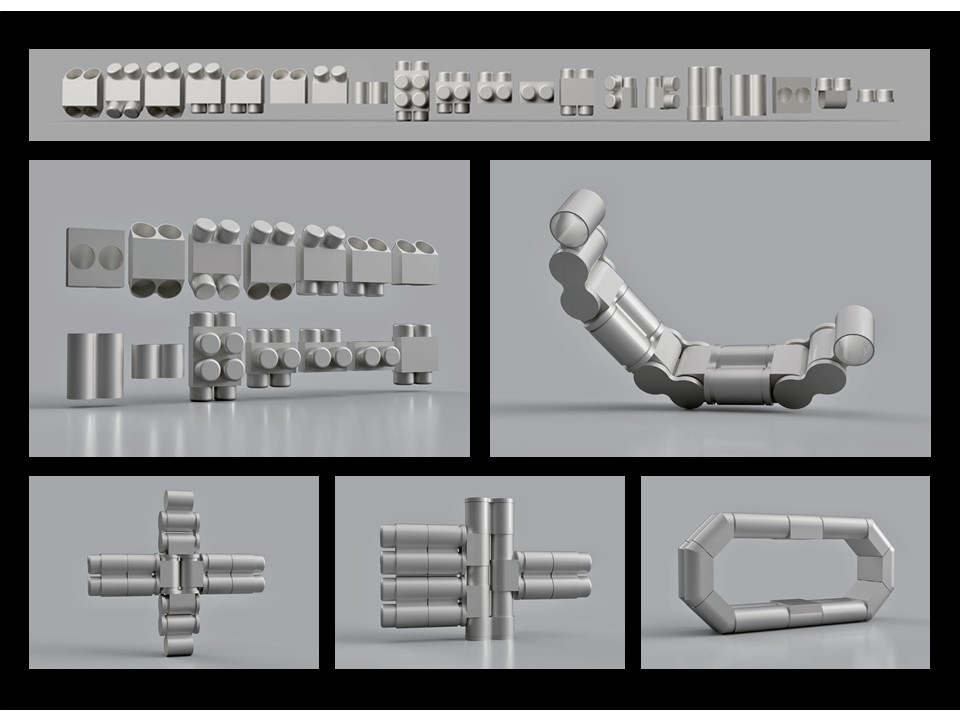

Teramoto Yutaka “B BLOCK QUANTUM”

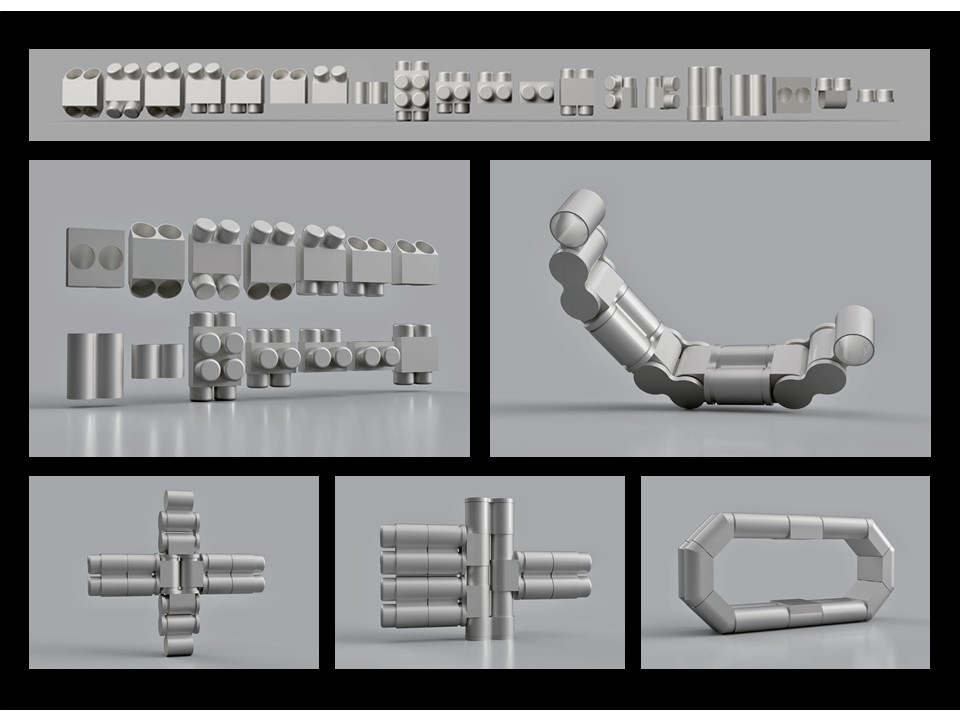

Twenty types of parts have been devised that allow for angled connections such as 45- and 90-degree joints as well as movable joints. To give the blocks a more mechanical appearance, multiple inclined parts have been prepared, allowing users to enjoy complex structures and movements. Connections are designed not only between convex and concave parts, but also between concave parts. The system accommodates the highly detailed and maniacal creations of adults.

Kawana Yasumu “CORE”

Because the basic B BLOCK system consists of a single type of piece and is limited to linear structures stacked upward, new pieces were devised to enable radial and curved forms. With a core element, it becomes possible to create spinning tops, enabling new forms of play such as the dynamic movement of colors during rotation and competitive play.

From Problem-Solving to Experiential Value Creation

The seven proposals, which were created over a long period of time, not only expanded the formative qualities of B BLOCK, but also included a variety of expansion keywords such as “inclusive experience,” “learning about man-made and natural objects,” “intergenerational family communication,” and “adult pastime.” The ideas proposed also show the potential to engage entirely new user groups for B BLOCK, going beyond so-called block play and integrating it into everyday life, thereby dynamically developing the value of new experiences.

Looking back on the project, Associate Professor Yamazaki commented as follows:

“This year, rather than focusing on the word ‘play,’ we paid close attention to the relationship between people and blocks, and with the theme of expanding that relationship, the students’ thoughts and free, original imaginations were embodied.

The attempt involved thinking about new ‘parts’ to add to B BLOCK, while at the same time giving concrete form to new ‘actions’ (manners and gestures) to be added. In other words, rather than aiming for a problem-solving design that addresses a limited task, the goal was to expand the design of experiential value that would lead to ‘new joy.’

Each student moved beyond the uniform notion of B BLOCK as a ‘children’s plaything’ and imagined what kinds of people it would engage, how it would make them feel, and what kinds of ‘joy’ it would lead to, passionately exploring the possibilities of the B BLOCK they themselves desired.

At a time when people must face uncertainty about the future, ‘play’ is something that enables humans to enjoy themselves, care for others, and remain true to their beliefs in each moment. At the same time, this project also gave us a strong sense of the further potential inherent in the value of B BLOCK.”

Humans have minds, and as we experience a variety of things every day in our various environments, we are constantly aware of the inner movements of our minds. We are creatures for whom experience and emotion are inseparable. In creating experiential value, as attempted in this project, we took the approach of “(1) observing experiences by starting from the movements of one’s own mind, (2) visually expressing the scene of the experience that resonated most deeply with one’s heart, and (3) concretely designing what would realize that scene.” This approach will likely become increasingly important in an era in which humane and richly textured design is in ever-greater demand. We believe that the fact that “play” was positioned as the primary theme of this collaborative research is of great significance.

Finally, I would like to take this opportunity to express my deepest gratitude to everyone at JAKUETS for providing us with this valuable research opportunity, and for consistently contributing their professional expertise—not only by offering opinions and advice on the students’ designs, but also by giving lectures on related publications and real-world design practices at all seven joint research sessions as well as the final presentation.

(Project Manager / Part-time Lecturer, Department of Design, Tokyo University of the Arts

Harumi Kusumi)